Take it from a local Moabite: there’s no such thing as fun for everyone … unless you’re in Moab, Utah, a small town hub for outdoor adventures, tours, guided trips, National Parks, State Parks, natural and cultural history, dive-bar nightlife—do we really have to go on? Even us locals have a Moab bucketlist miles long. This list of 50 things to do in Moab, Utah, is in no way exhaustive, but will provide you with a good jumping off point as you plan your trip—or as you find yourself driving down Highway 191 toward the heart of town.

50 Things to do in Moab, Utah: written by a local

A few travel tips before we dive in! Moab is hot in the summer and cell service can be spotty outside of town. Bring lots of water and a lunch if you’re going on a day hike, and download your maps. This might be a hot take, but it’s worth booking a hotel room for access to the pool and hot tub (nothing better than soaking sore muscles at the end of a long day!).

–National and State Parks–

1. Arches National Park

We know you know this one. But

Arches truly is worth every second you spend in the park: the landscape is so utterly fascinating, so unlike anything you’ve seen before. Delicate Arch is popular for a reason. And if you’re up for it, the 8-mile Devils Garden Primitive Loop Trail is a great way to spend the day.

2. Canyonlands National Park

Did you know Canyonlands National Park is split into districts? It’s just that big. The two most accessible are the Island in the Sky and Needles districts; Island in the Sky is closer to Moab. If you’re visiting I-Sky, make sure you stop by Mesa Arch (again, popular for good reason), and Aztec Butte. If you’re heading down to the Needles District, stop at Newspaper Rock along the way to see hundreds of petroglyphs, and spend the rest of the day hiking out to Druid Arch.

3. Dead Horse State Park

A gorgeous drive and even more gorgeous overlook.

–Knock something off your bucketlist–

4. Book a rafting trip down The Daily

The Daily stretch of the Colorado River is a great beginner’s whitewater trip: the rapids range from class I-III, especially if the water is high (for high water, visit in May or June).

5. Rent mountain bikes and explore the Bar M trail system

Mountain biking is fun! Don’t be intimidated by the shredder content you see online: in my opinion, mountain biking is one of the most playful sports you can do. And if an obstacle is too big, just walk it—you’re not bikin’ till you’re hikin’, as they say. Bar M is a great place to start – take a few hours and try the Rusty Spur, Bar M loop, and Lazy-EZ trails.

6. Take on Hell’s Revenge

Hell’s Revenge is one of the most popular off-roading trails in the Moab area—and dare we say, the world? If you want to see this trail for yourself, you can chat with outfitters in town to rent vehicles for a self-guided experience, book a guided tour, or hop in a massive, open air Hummer to let a guide drive the trail for you.

7. Try rock climbing at Wall Street or the Cinema

Moab is a haven for rock climbers—and many of those climbers work as guides, offering tours to, literally, show visitors the ropes. Book an experience with a climbing outfitter to really get to know the Moab sandstone.

8. Get splashed through Westwater or Cataract canyons

If The Daily isn’t enough oomph for you, book a rafting trip down Westwater Canyon or Cataract Canyon to experience huge rapids (and huge thrills!).

9. Rappel into a slot canyon

If you’re scared of heights, this experience probably isn’t for you. But if you want to explore the hidden and hard-to-get-to sides of Moab’s landscape, book a canyoneering tour with a local outfitter.

10. Take a mini beach vacation at the Mill Creek Waterfall

Moab sits on an important piece of landscape within the Colorado River watershed—which is a fancy way of saying that we have multiple creeks that run from the La Sal mountains, through town, and into the Colorado River. The Mill Creek waterfall hike is one mile each way, and drops you at a lovely little swimming hole.

11. Camp at Oowah Lake in the La Sal Mountains

If it’s too hot in Moab, escape to the nearby mountains like the locals do. You can also fish in Oowah Lake, so bring a rod!

12. See Moab from the sky

It’s hard to understand just how vast this desert landscape is until you see it from above. Treat yourself to an air tour on an airplane or helicopter to get a new perspective on the canyons you’ve explored from the ground!

13. Live our your cowboy dreams

Horseback riding is another popular way to change your perspective on the Moab landscape.

14. Go “set-jetting” around landscapes featured in Western films

Did you know the Moab to Monument Valley Film Commission is one of the oldest in the world? Head out Highway 128 and you’ll recognize the landscape featured in movies like Wagon Master (1950) and Horizon: An American Saga (2024).

15. Take a night hike

Moab is a certified dark sky community – and is surrounded by the official Dark Sky Parks of Arches National Park, Canyonlands National Park, and Dead Horse Point State Park. Book an astronomy tour to explore the stars with a local expert, attend a star party at a nearby park, or just wait until darkness falls to see some of the best stars in the world.

16. See dinosaur tracks

The Mill Canyon Dinosaur Tracksite boasts tracks of eight different dinosaurs who stomped across this patch of land when Utah was part of a vast inland sea in the Jurassic period. Well-written interpretive signs help tell the story of the dinosaurs, and a boardwalk allows visitors to explore every track.

17. Drive the Upper Colorado River scenic byway

If you’ve never driven Highway 128, you’re in for a real treat. The 44-mile stretch of road takes visitors from the town of Moab along the Colorado River, passing by Castle Valley and the Fisher Towers. You’ll watch the landscape open up and morph as you wind your way to the end of the scenic byway at Dewey Bridge.

18. See petroglyphs

There’s something really special about petroglyphs: about looking at stories carved into sandstone thousands of years ago. Easily accessible sites include a site along Potash Road and the Birthing Scene petroglyph off of Kane Creek road.

19. Take an adrenaline-filled leap

Soar through the skies by leaping from a plane – or cliff! In Moab, you can book a skydiving experience, a BASE jump off a cliff, or swing off the world’s largest rope swing.

20. Go on a scenic tour

Let a local expert take the wheel to guide you through all of the must-see sights in Moab.

–Explore the landscape on must-do trails–

21. Corona Arch Trail

This arch is massive – 140 by 105 foot opening! – and the hike is fun, with a section that requires visitors to use a ladder and safety cable.

22. Fisher Towers Trail

The Fisher Towers are composed on Moenkopi and Cutler sandstones that have eroded into fantastical shapes! Allow four hours if you’d like to do the whole trail.

23. Grandstaff Canyon Trail

The Grandstaff Canyon trail leads to the magical Morning Glory Natural Bridge, winding along a creek to do so. Look out for poison ivy!

24. Hidden Valley Trail

Ascend a steep incline to find hidden valley, a valley tucked on top of the Moab Rim. This is an out and back trail – scamper along the valley for as long as you feel like it.

25. Juniper Trail

The Juniper Trail is a small loop located within the Sand Flats Recreation Area that leads visitors on a scavenger hunt looking for native flora and fauna.

26. Longbow Arch

A fun little trail located at the Poison Spider parking area that leads to the 60 foot Longbow Arch.

27. Moab Rim

Want to see sweeping views of Moab and the Colorado River? Hike up the Moab Rim Trail! This trail is tough – it’s pretty steep – but the views are worth it.

28. Amphitheater Loop

A 3 mile loop starting at the Hittle Bottom campground on Hwy 128 that requires a small gully scramble.

29. Dellenbaugh Tunnel

This trail leads to a long, tunnel-like arch.

30. Hunter Canyon

Hunter Canyon is a lovely walk: the canyon stretches for 2 miles before reaching the end. Look for the large arch on the right-hand side of the canyon about half a mile from the trailhead.

–In town–

31. Learn local history

Visits to the Moab Museum and Moab Giants are always worth it: we guarantee you’ll learn something new and surprising! Look out for special events and programs hosted by the Moab Museum, too.

32. Attend an arts or music festival

The shoulder seasons boast a number of cultural events, including the Moab Folk Festival, Moab Music Festival, Red Rock Arts Festival, and Moab Arts Festival.

33. Grab a milkshake at Moab’s oldest restaurant

Today, Milt’s Stop and Eat is just as popular as it was when it first opened in 1954. Grab a classic milkshake, fries, and a burger – and know that Milt’s sources as many ingredients as they can from local food producers!

34. Cap off your night with a visit to Moab’s dive bar

Locals will laugh that I’m including Woody’s Tavern on this list. Moab doesn’t have a ton of nightlife – it’s hard to get a liquor license in Utah – but Woody’s is always fun, and on the weekends often hosts local bands to play live music.

35. Peruse local art

Moab is an artistic haven – you can’t help but to be inspired here. Visit Moab Made and Gallery Moab to buy souvenirs and art made by only local artists.

36. Find something for everyone at the Moab Food Truck Park

You’re coming back into town from a morning hike, searching for lunch, but no one can agree where to go? The Moab Food Truck Park is home to individually owned and operated food trucks, offering a wide range of food, and a centralized place to eat.

37. Customize your Moab swag at the T-Shirt Shop

Print customized designs, ranging from silly to artistic, on any color t-shirt, sweatshirt, tanktop, long sleeve, hat, you name it.

38. Try a “dirty soda”

The dirty soda is a Utah-born beverage trend: it’s a soda base spiked with add-ins like cream, syrups, and fruit juices. Lops Pop Stop is our local dirty soda shop – get the Moab On the Rocks (Coke, cherry syrup, coconut milk, lime juice) and pretzel bites.

39. Read books by local authors

Back of Beyond Bookstore, which is independently and locally-owned, specializes in natural history and regional titles of the Colorado Plateau. But they also boast an impressive collection of popular fiction and rare acquisitions.

–Hidden Gems–

40. Swim at Ken’s Lake

Take a rest – spend a day at Ken’s Lake, a small, man-made lake just south of Moab. The lake allows dogs, fishing, and watercrafts. There’s also a campsite nearby!

41. Spend the day at Warner Lake

If Moab is too toasty, head into the La Sal Mountains. While camping near Oowah is a must, like we mentioned, a day spent at Warner Lake – fishing and exploring the nearby sections of the Whole Enchilada Trail – is never wasted.

42. Mountain bike the Raptor Route

The Raptor Route is a set of trails within the Sand Flats Recreation Area that provide an alternate exit to the Whole Enchilada trail – but are also just a ton of fun to do by themselves. Do the whole thing – Eagle Eye to Kestrel Run – or just try Falcon Flow if you’re looking for a fun, flowy, blue-black mountain bike trail.

43. Listen to live bluegrass music or catch a magic show at the Backyard Theater

The Backyard Theater is truly a Moab gem – a little stage tucked behind Zax restaurant, the Backyard Theater hosts free bluegrass music every Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday night, and a magic show on Saturdays ($10). Bring a picnic dinner – outside food and drink are welcome – and utilize the dance floor.

44. Challenge yourself to run a race

Moab is home to tons of running races at a variety of distances, from 5Ks to the legendary Moab 240. There’s no better place to run a half marathon than on Moab trails.

45. Thrift your new favorite shirt

Moab has excellent thrift stores, including WabiSabi, Underdog Thrift Store, Moab Gear Trader, and Radium Alley Thriftique.

46. Drink from a natural spring

The legend around Matrimony Springs – a natural spring located on Highway 128 – is that if you drink the water, you’ll never leave Moab.

47. Sled the sand dune

The giant sand dune located on the other side of the highway from the entrance gate to Arches National Park is hard to miss. Bring a sled, or just walk up and roll down the dune – and see if you can make the trek up to the very top!

48. Play in a park

The Moab landscape is its own playground – but if you need a place for kids to run around, head to Rotary Park (which has a playground, volleyball net, basketball court, gazebo, and musical structures that kids and adults will have a blast experimenting with) or Lions Park (which is home to a playground and bouldering structures).

49. Get hands-on with local geology – and take it home

In 1960, Lin Ottinger – a uranium miner turned tour guide – opened the Moab Rock Shop, a treasure trove of rocks, minerals, and fossils. Many of Ottinger’s discoveries have been donated to museums and universities, but others are hosted in the rock shop!

50. Fall in love with a Moab local and never leave

Only slightly joking.

By Science Moab, originally published on Soundcloud and with KZMU and the Moab Sun News

From the perspective of an archaeologist, the physical body of an ancient person is a gift because a body is a time capsule of the past. They lived in that space and that time, and their bodies are manifestations of what was there. We talk with archaeologist Erin Baxter, teacher and Curator of Anthropology at Denver Museum of Nature and Science, about her work unraveling the ancient southwest culture and her fascination with the archaeology of death.

Science Moab: What is the relationship between archaeology and anthropology?

Baxter: It depends on where you study anthropology. If you study it in Europe, you actually major in archaeology. If you study it in the United States, you study anthropology with sub-disciplines. So if you can imagine a big umbrella that is anthropology, under that fits four different fields: linguistics, biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, and archaeology. Linguistics is the study of language, cultural anthropology is the study of living groups of people, biological anthropology is the study of the body and how it evolved, and archaeology is the things that people have left behind.

Science Moab: What part of the interactions of these sciences do you enjoy most?

Baxter: I love the archeology bit – that’s what got me into it. It’s outside, it’s teamwork, it’s problem solving, it’s mystery-finding, and it’s interactive. As I’ve gotten into Southwest archaeology I’ve realized that archaeology doesn’t stand alone.

I’m particularly interested in the practice of ancient burial practices, and… there’s a long history of archaeologists behaving not as we should with human remains. But what I’ve learned is that I work with biological anthropologists who study the body, and then I [also] work with Indigenous descendant communities, and their wishes and their own histories and oral histories about how ancient people lived. We can’t stay in our bubbles. We’re still learning to be the best archaeologists we can be. We’re not great at it yet, but we are miles better than I think we were 100 years ago. So it’s a learning process every day and it’s relationship building.

Science Moab: Tell us about your research on death.

Baxter: I don’t love death, but… a body is a time capsule of the past: [that person] lived in that time and their bodies are manifestations of what was there. So not only can you learn sex, we can learn about height, we can learn general health, if they were injured or maybe had a disease—all of those are written in the bones. We can also now learn more things and this is where science is really fascinating. DNA studies give us hugely important information about migration patterns, occupations, and relationships of individuals across time and space.

Science Moab: So you’re trying to uncover clues and the mystery of how these ancient people lived. How do you go about doing that, scientifically? What are you looking for?

Baxter: My research question when I was in school was [about] how ancient people in the US Southwest lived. You go to…where many descendant communities live to this day… Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and 23 living tribes in New Mexico and Arizona and others…and you see [Ancestral Puebloan sites like] Mesa Verde or Chaco Canyon or Wupatki and you sort of can’t imagine what it was like.

I wanted to get at the hierarchy of the ancient past… was there one, is it testable?… We can see hierarchy in the archaeological record. People who are better off are physically healthier, they’re taller since they have access to better foods, better proteins. They tend to live in bigger houses, and they tend to be buried with nicer things. Those are three really simple ways of [looking at the question].

There are other ways to approach these questions. If you look at a place like Chaco Canyon, which has 12 buildings called great houses of five stories, [with many hundreds of] rooms—one great house, Pueblo Bonito, was the biggest building in the United States until about the 1880s when a [larger] tenement was built in New York City. You would think that might be a place where lots of people lived, but we don’t see a lot of trash, or burials, or other stuff there. So people living in big houses that [don’t show those signs of occupation]…who are those people? The hypothesis was that those are people who are in charge of things who are important for a variety of reasons.

I think in our Western, white nation, when we see museum displays about Native American communities, there is stagnation without vibrancy and color. There has been the myth of stasis—a myth of a group of humans who haven’t changed much over time. But yet there are histories with hierarchies, kings and queens, witchcraft, death and violence and unpleasant things. Unpleasant things, unfortunately, are the ones that [tend to] show up in the archaeological record. But, with those unpleasant things, you imagine the really lovely things that might have come on the other side of that. You can see the vibrancy of history.

I thought, by studying the hierarchies and the power structures of ancient groups of people, you might actually [be able to] return a [piece] of what a Westerner would call ‘history,’ which we’ve whitewashed for a variety of reasons… to colonize, to subjugate. But you have to do that not as a white person, you have to do that as a collaborator. And so these studies become complicated.

I think I have arguments to be made for [a record of hierarchy in these ancient societies], but my arguments come from historical burial data found by people who dug this 100 years ago…white archaeologists, largely from the East Coast…and it’s not okay to talk about that [because] I am not of the position or internal to various groups of tribal representatives to be able to say that. So, it’s science, but it’s science with a level of 20th and 21st-century complexity that comes from our colonial past. In the post-colonial world, where do we [white archaeologists] fit in?

It’s going to take relationship building, and I think it’s going to be interesting to publish on this [question] one day when trust has been rebuilt. I think archaeologists in the 21st century are making great strides to do that because we’ve got a lot to make up for.

Science Moab is a nonprofit dedicated to engaging community members and visitors with the science happening in Southeast Utah and the Colorado Plateau. To learn more and listen to the rest of Tim Graham’s interview, visit www.sciencemoab.org/radio. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Watch Tim Graham explore pothole ecosystems with Discover Moab!

Have a press release or story you’d like to see published on Discover Moab? Email asst. marketing director Alison Harford at aharford@discovermoab.com.

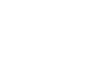

Marjorie “Mardy” Dawn Thomson (Center, Uranium Queen), Nancy Elizabeth Nault (left, attendant), Hallene “Hally” Thorne (right, attendant). Hally’s helmet reads “Uranium Days, 1956.”

Marjorie “Mardy” Dawn Thomson (Center, Uranium Queen), Nancy Elizabeth Nault (left, attendant), Hallene “Hally” Thorne (right, attendant). Hally’s helmet reads “Uranium Days, 1956.”

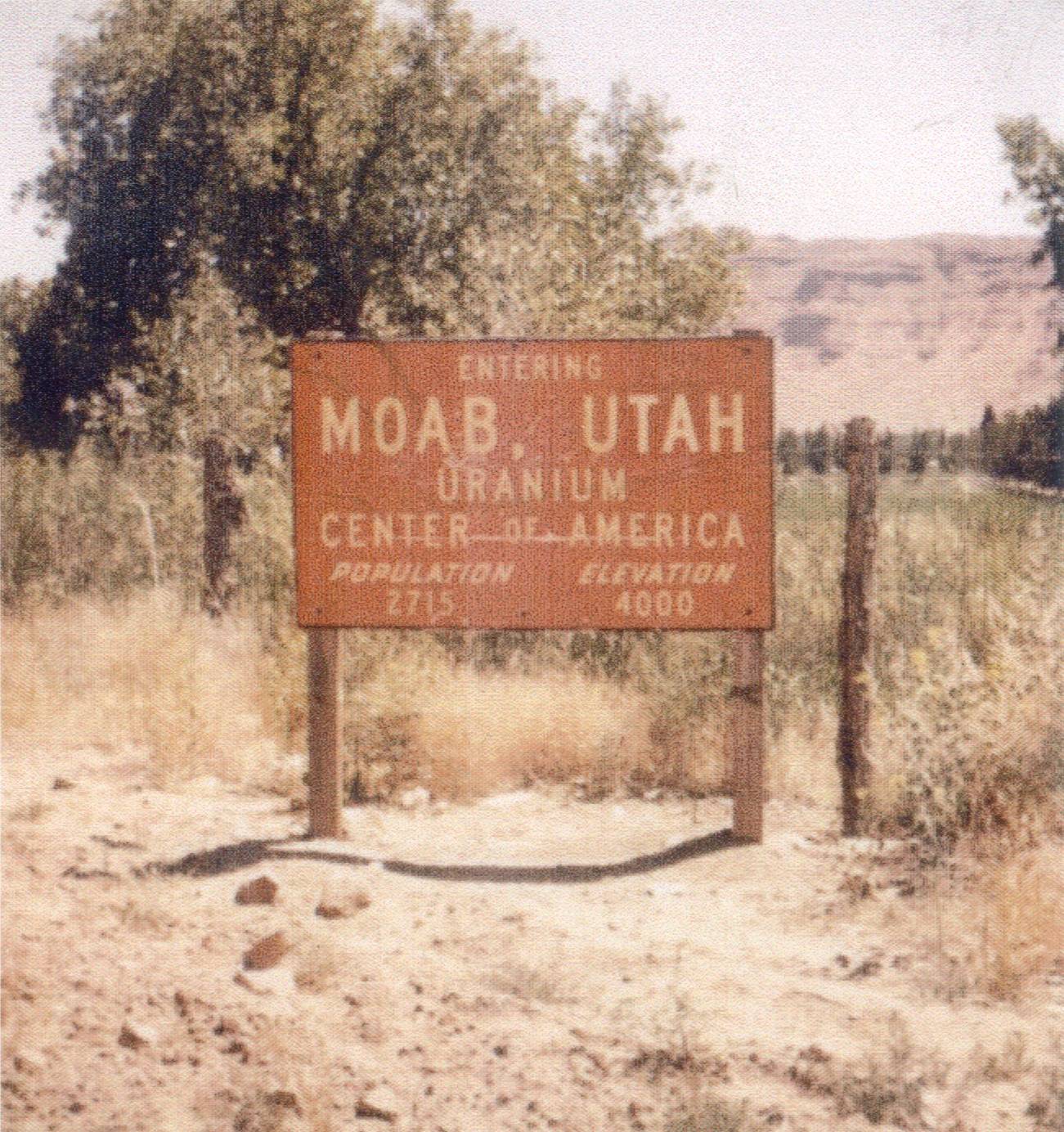

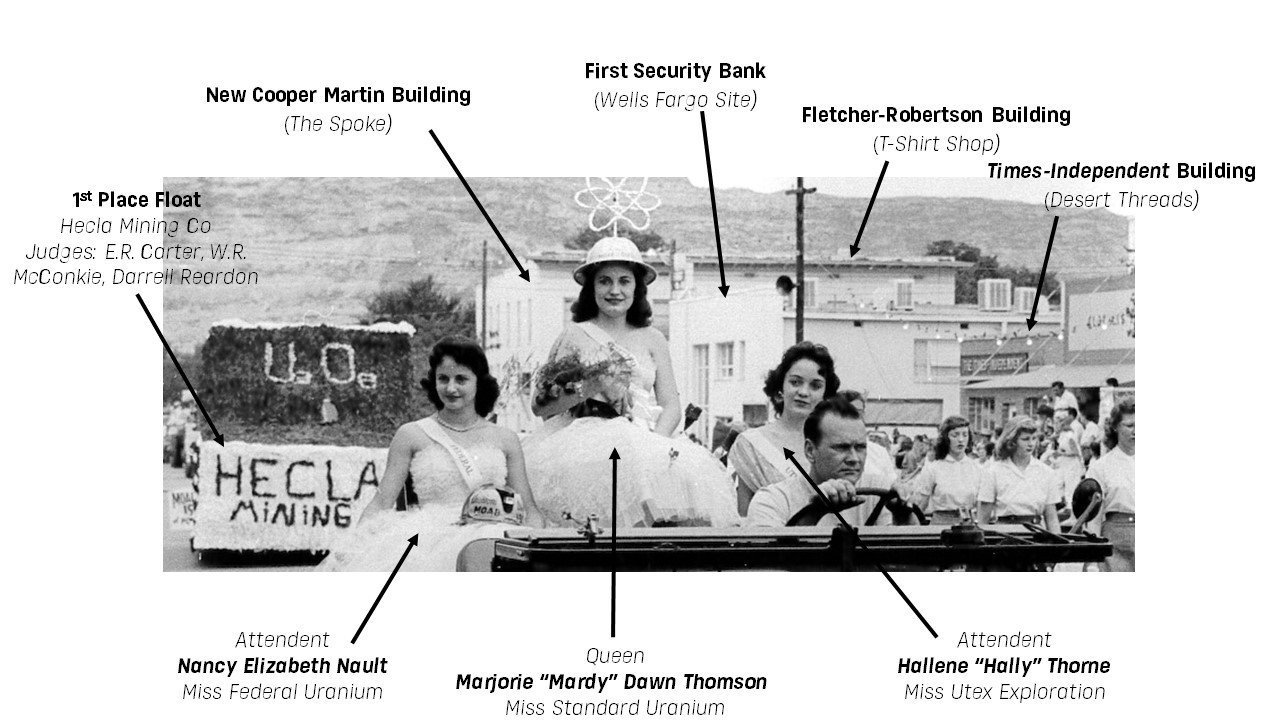

Uranium Days 1956: The celebration

For several years beginning in 1956, Moab hosted an annual festival dubbed “Uranium Days,” which celebrated the town’s booming wealth and growth on account of uranium mining. This short-lived celebration was established to compete with events like the Green River Melon Fest and various other festivals occurring around the state. The first event was held on August 17 and 18 in Moab.

The Times-Independent reported on August 23, 1956, “Uranium days hit Moab in full force on Friday morning and were there very much in evidence until late Saturday night. It was two full days of parades, programs, dances, and merchandising events for Moab’s residents and visitors from out of town, and judging from the large crowds, and feeling of excitement from people on the street, the first of what is hoped to be an annual event was a huge success.” Uranium Days, however, would sadly be held for only four years, with the last court serving in 1960.

The inaugural Uranium Court

One of the highlights of the event was the naming of the Uranium Queen and her court. Eight contestants, each sponsored by an independent mining company, vied for the “honor of reigning over the two-day celebration,” according to the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel on August 16, 1956.

“Friday evening the festivities got underway with the crowning of the Queen,” the Times-Independent reported on August 23. The contestants would compete later in the State Dairy Princess contest at the State Fairgrounds later in September of that year.

Marjorie “Mardy” Dawn Thomson (b. 1936), Miss Standard Uranium, was named the inaugural Uranium Queen in 1956. She later married William H. Lewis in Moab. Nancy Elizabeth Nault (b. 1939), Miss Federal Uranium, was named Mardy’s attendant (left in the image) and later married Moab’s Garry Joe Day. Hallene “Hally” Thorne (b. 1939), Miss Utex Exploration, was named Mardy’s second attendant (right in the image) and later married Olin T. Glover in Moab. All three attended Grand County High School; the two attendants graduated in 1958 and the queen graduated a year earlier.

The 2023 mural

In October 2023, Dr. Chip Thomas, a photographer, public artist, activist, and physician who has been working on the Navajo Nation since 1987, installed a mural supported by the Moab Arts and Recreation Center on the Moab Museum building on Center St. The photo, a selection from the Moab Museum Collection, displays the 1956 Uranium Queen and her attendants riding a vehicle riding down Center Street in the Uranium Days Parade.

Pictured in the image are the 1st place float by Hecla Mining Co., the New Cooper Martin Building (where the Spoke currently resides), First Security Bank (at the current Wells Fargo site), the Fletcher-Robertson Building (now home to The T-Shirt Shop), and the Times-Independent building, where Desert Threads currently resides.

Explore Moab’s uranium history through the new U92 exhibit!

U92 Moab’s Uranium Legacy opens FREE to the public on Saturday, February 15th, with programming from our partners from 11 am to 3 pm. Visitors are invited to explore a transformed Museum space and immersive exhibition following the boom and bust of our town which found itself at the center of the Cold War. Activities and community history opportunities with the Department of Energy, Utah Historical Society, the MARC, and Moab Museum staff will be hosted on the lawn.

Moab Museum Uranium Memories Project:

Share your uranium story, and join us in kicking off a year-long effort to tell a more complete uranium story with the Uranium Memories Project! Visitors are invited to share their own memories, or memories of loved ones involved in uranium mining or milling, to help us tell the story of Moab and add new perspectives to the Moab Museum’s Oral History Collection. At this table, participants may share a short story or schedule time to conduct a full oral history interview. This program has received funding from Utah Humanities and Utah Historical Society.

Utah Historical Society Scan & Share: (registration)

Visit with the Utah Historical Society to preserve and share your historical materials related to your connection with Moab’s uranium history. Bring up to ten of your photos, documents, letters, art, and other items to be scanned, digitized, and added to the Peoples of Utah Revisited online collection. These items can be historical or contemporary: from long ago to yesterday! *All of your items will be returned to you after they are scanned on the day of the event.

Department of Energy:

Environmental Management: Representatives from the Department of Energy Office of Environmental Management and Moab’s Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) Project will be present. Visitors will also make and decorate seed balls using native seeds from the region.

Legacy Management:

Radiation is all around us, all the time, from natural and human-made sources. With the Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management, visitors will have the chance to learn what radiation is, the difference between ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and the different types of radiation by safely exploring everyday items and examples of radiation.

MARC:

Join the staff of the Moab Arts and Recreation Center in a paint-a-square mural project! Visitors are invited to paint a small watercolor square to contribute to a larger recreation of a historic photograph from the Museum’s collection.

Have a press release or story you’d like to see published on Discover Moab? Email asst. marketing director Alison Harford at aharford@discovermoab.com.

Contact: Tara Beresh, Curatorial and Collections Manager, tara@moabmuseum.org

435-259-7985

For immediate release

[Moab, UT] – With a FREE public opening from 9 am – 5 pm on Saturday, February 15, 2025, the Moab Museum opens a new exhibition that transforms the gallery space —

U92: Moab’s Uranium Legacy. Audiences will be Immersed in Moab’s uranium boom, a time which sparked a “frenzy” that lured thousands to Moab and a subsequent boom of the town that elevated Moab to the “richest town in America” for a short while.

The first phase, opening in February 2025, highlights the Cold War-driven uranium boom, the people who lived it, and the vibrant yet challenged infrastructure that emerged. The second phase, debuting in July 2025, draws on first-person accounts to explore the enduring environmental, health, and cultural impacts — and future consequences.

Visitors will follow the contributions of notable figures, both well-known and unsung, who played key roles during this important moment in American history. Alongside personal narratives of “boom,” visitors learn about the “bust” that launched the modern recreation economy and serves as a testament to Moab’s unwavering resilience.

Many uranium miners have passed, taking their memories with them; those still living are in their eighties and nineties. The Museum team has engaged many individuals and their families to capture first-hand accounts of life in Moab during the uranium frenzy that forever shaped the community. Collaborations with the Atomic Legacy Cabin in Grand Junction and scientific support from the Uranium Mill Tailings Remediation Action (UMTRA) project have been essential to ensure historical accuracy and enrich the exhibit narrative.

Every shared memory helps us understand more fully what Moab’s uranium era meant to those who lived it. We’re especially grateful for insights from the many community members who contributed stories that add depth and authenticity to the exhibition. This exhibition is a tribute to their legacy as much as it is a chronicle of Moab’s past.

U92: Moab’s Uranium Legacy opens to the public on Saturday, February 15, 2025. If you or someone you know is willing to share stories from the uranium era, we would love to hear from you; Please reach out to Tara (tara@moabmuseum.org) or Allie (allie@moabmuseum.org) at the Museum.

Events during the exhibit opening

U92 Moab’s Uranium Legacy opens FREE to the public on Saturday, February 15th, with programming from our partners from 11 am to 3 pm. Visitors are invited to explore a transformed Museum space and immersive exhibition following the boom and bust of our town which found itself at the center of the Cold War. Activities and community history opportunities with the Department of Energy, Utah Historical Society, the MARC, and Moab Museum staff will be hosted on the lawn.

Moab Museum Uranium Memories Project:

Share your uranium story, and join us in kicking off a year-long effort to tell a more complete uranium story with the Uranium Memories Project! Visitors are invited to share their own memories, or memories of loved ones involved in uranium mining or milling, to help us tell the story of Moab and add new perspectives to the Moab Museum’s Oral History Collection. At this table, participants may share a short story or schedule time to conduct a full oral history interview. This program has received funding from Utah Humanities and Utah Historical Society.

Utah Historical Society Scan & Share: (registration)

Visit with the Utah Historical Society to preserve and share your historical materials related to your connection with Moab’s uranium history. Bring up to ten of your photos, documents, letters, art, and other items to be scanned, digitized, and added to the Peoples of Utah Revisited online collection. These items can be historical or contemporary: from long ago to yesterday! *All of your items will be returned to you after they are scanned on the day of the event.

Department of Energy:

Environmental Management: Representatives from the Department of Energy Office of Environmental Management and Moab’s Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) Project will be present. Visitors will also make and decorate seed balls using native seeds from the region.

Legacy Management:

Radiation is all around us, all the time, from natural and human-made sources. With the Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management, visitors will have the chance to learn what radiation is, the difference between ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and the different types of radiation by safely exploring everyday items and examples of radiation.

MARC:

Join the staff of the Moab Arts and Recreation Center in a paint-a-square mural project! Visitors are invited to paint a small watercolor square to contribute to a larger recreation of a historic photograph from the Museum’s collection.

Have a press release or story you’d like to see published on Discover Moab? Email asst. marketing director Alison Harford at aharford@discovermoab.com.

The view of the Colorado River from the Moab Rim Trail.

The view of the Colorado River from the Moab Rim Trail.

By local experts at Discover Moab

My favorite place in the world is just a few minutes outside of downtown Moab, Utah. I turn off Main Street at Kane Creek Boulevard, a street that winds past the movie theater and through a few small neighborhoods before it lands next to the Colorado River. The road leads to campsites, canyons, hiking trails, biking trails, petroglyphs, off-road routes, climbing crags – Kane Creek Boulevard is one of Moab’s hidden gems, and it’d be easy to spend days here, especially if you snag a camping spot. It’s well-worth adding a day to your Moab trip just to explore this unique zone.

Something to keep in mind with activities down Kane Creek: there is very spotty cell service in this area! Download your maps beforehand and consider bringing a satellite communications device.

And another note: many of the trails get very hot in the summer – there isn’t a ton of shade out here – so be ready for the weather and bring snacks and water with you.

Places to camp along Kane Creek: Kings Bottom, Hunter Canyon/Spring Canyon, The Ledge

Things to do along Kane Creek Boulevard – choose your own adventure style

Hike or off-road the Moab Rim Trail

Keep an eye out for a trailhead shortly after the road turns left and starts following the Colorado River. This is the Moab Rim Trail, a hiking and off-roading route that offers stunning views of the Colorado River and the town of Moab. It’s one mile to reach the stop, but it’s a steep mile – the hiking route is called

“The Escalator” for a reason. Watch for local Moabites who run it.

Explore Moonflower Canyon

Just after Kings Bottom campground is Moonflower Canyon, which provides a shaded and cool walk through a beautiful, tree-lined canyon. This canyon floods during monsoon season in late summer: when you make it to the end, peer up at the canyon walls and you’ll get an idea of how large the cascade of water falls down into the canyon.

Before leaving the parking lot, head over to the right side (as you’re looking at the canyon) to spot your first petroglyphs of the day. Here’s

what to know about petroglyphs before you go.

Hike or off-road at Pritchett Canyon

Pritchett Canyon provides another thrilling off-road or hiking experience. It’s the hardest off-road trail in Moab, so you may prefer to hike it–hiking three miles (six out and back) will get you near a number of arches and bridges formed in the rocks. The start of the canyon passes through private land, so you have to pay a small fee. These trails are a bit harder to follow, so make sure you do your

research beforehand.

Explore Jackson’s Trail

Park at a large parking lot just past Pritchett Canyon for access to Jackson’s Trail. This is a bike-accessible trail as well, but mountain bikers will be coming down the trail, so keep an eye out for them as you explore. The

trail follows the Colorado River for a mile or so, then switchbacks its way up to the top of a mesa, where it’ll connect to a few other trails. Stop here to take in views of the river, or continue on to the Rockstacker trail to find Pothole Arch. Beware of getting lost, and of a short icy stretch in the winter.

Bike, hike, climb, off-road, and watch basejumpers at the Amasa Back/Captain Ahab/Hymasa trailhead

Pull off at the Amasa Back/Captain Ahab/Hymasa trailhead on a nice, not-windy day and you’ll likely be able to spot basejumpers leaping from Tombstone Rock across the road. This trailhead is a hub of activity: It leads to a world-class mountain biking trail system and a popular off-road route. The most popular mountain biking trail accessible here is

HyMasa/Captain Ahab: if you’re an expert-level mountain biker, this trail is not to be missed. Thousands of bikers come to this area each year to experience it! If you’re not on a bike, this trail makes for a lovely hike or trail run as well. You’ll likely pass by off-roaders testing their skills along the Cliffhanger road.

Rock climbers can also spend a few hours enjoying the

Abraxas Wall, accessible from this trailhead, which has 10 trad climbs ranging from 5.10 to 5.11d.

This is a good spot for a picnic lunch!

Peer into the past at the Birthing Scene petroglyph

One of the most captivating petroglyphs in Moab (in this writer’s opinion) is the birthing scene petroglyph, which was carved onto a large boulder. The petroglyph shows, as you can guess, a birthing scene: there are two humanoid figures depicted, along with depictions of feet and animals. It’s a beautiful glimpse into the past and the lives of the people who first lived in this area.

Remember: do not touch the petroglyphs! We want to

preserve these rocks as long as we can. Scratching on rocks causes irreparable damage and is illegal.

Scramble up to Funnel Arch (only if you have route-finding skills)

Continuing past the Birthing Scene petroglyph, you’ll find a small pull-off on the road to the left. This is the small trailhead to the Funnel Arch trail, a short and fun trail that leads to an impressive arch. This trail requires significant route-finding skills – the trail dips in and out of sight – and there’s a challenging rock climbing scramble right at the start.

Rock climb at the Ice Cream Parlor climbing wall

The

Ice Cream Parlor climbing wall offers 45 sport and trad climbs from beginner 5.7 routes to a few challenging 5.12 PG13s. It’s south facing, so if you plan to climb, get here early to avoid the scorching sun – or visit during a sunny winter day, when the warm rock provides balmy respite from cold temperatures. This wall truly provides something for everyone, no matter what skill level climber you are.

Continue on to watch the canyon open up into a wide desert landscape – and find a few more camping options

The Ledge campsites are further down the road. Past here, the road turns into a 4×4 road – off-roaders will enjoy going through Hurrah Pass and along Lockhart Basin road as part of the

Chicken Corners route.

Charlie Glass atop a horse. [Moab Museum Collection]

Charlie Glass atop a horse. [Moab Museum Collection]

Throughout Black History Month in 2023, the Moab Museum dug into its collection to highlight stories of prominent Black individuals and groups throughout the history of the Moab Valley. In this column, Charlie Glass takes center stage: a Black local Moab cowboy who worked at the Turner, Osborn, and Cunningham ranches. This cowboy was known for his grit and ingenuity, qualities admired during his time pushing cattle from Moab to Thompson Springs.

Glass was known for his fierce loyalty to ranch bosses, but his reputation was really made in 1921 during the Sheep Wars era, a time of conflict between sheepherders and cowboys. Glass found himself in an altercation with Basque sheepherder named Felix Jesui whose flock was encroaching on Oscar L. Turner’s property. Glass fatally shot Jesui and claimed self-defense. Glass’s bail was set at $10,000 (the equivalent of $157,000 today) which his boss, Turner, paid immediately and without question.

Cowboys drive Scorup-Somerville cattle. [Moab Museum Collection]

Cowboys drive Scorup-Somerville cattle. [Moab Museum Collection]

After a well-attended court hearing, Glass was acquitted and continued to work on the Turner Ranch for another 16 years. In 1937, Glass was playing poker with the cousins of the man he’d shot years before. After what local lore calls an amiable game, the group parted ways. But later that evening, Glass was found dead in the back of the men’s pick-up truck—reportedly, Glass’s neck was broken. The cousins claimed no foul play, but the truth of the night remains a mystery to this day.

Glass was buried in the Turner family plot, at a time when African-Americans were barred from being buried in the Fruita, Colorado, cemetery. Stop by the Moab Museum to view Pete Plastow’s portrait of Charlie Glass, mid altercation with Felix Jesui, who proved to be the ultimate end of the this local Black cowboy. .

The Moab Museum website has a

larger profile on Charlie Glass and a recording of “The Ballad of Charlie Glass,” performed by Sand Sheff in 2019 at KZMU Studios. The song was written and composed by William Leslie Clarke, courtesy of Three Rivers University Press.

The Moab Museum is dedicated to sharing stories of the natural and human history of the Moab area. To explore more of Moab’s stories and artifacts and find out about upcoming programs, visit MoabMuseum.org

Courtesy of the Moab Museum

Courtesy of the Moab Museum

The Moab Museum will be temporarily closing its doors from December 23, 2024, through February 10, 2025, as we prepare for the exciting installation of our newest exhibition,

U92: Moab’s Uranium Legacy. During this time, Museum staff and volunteers will be hard at work creating an immersive and educational experience that delves into the history and legacy of uranium mining in the Moab area.

While the Museum will be closed to visitors, we will host periodic volunteer days for those interested in supporting this important installation process. Community members are encouraged to get involved and be part of bringing

U92: Moab’s Uranium Legacy to life.

Mark your calendars for February 15, 2025, when the Museum will reopen with an all-day celebration of the new exhibition. Join us to explore the stories of miners, mill operators, entrepreneurs, and others who shaped Moab’s uranium boom and its lasting impact. Stay tuned for more details as we approach this exciting opening!

For updates and volunteer opportunities, visit www.moabmuseum.org or contact us at info@moabmuseum.org.

Gordon Fowler’s snowshoes [Moab Museum Collection]

Gordon Fowler’s snowshoes [Moab Museum Collection]

Summertime visitors to the Moab Museum may have difficulty understanding why there’s a pair of snowshoes on display in the Museum’s gallery. While the desert, of course, isn’t well-known for its snow, locals know that the La Sal Mountains outside of Moab can get quite snowy indeed.

Today, Moabites enjoy recreating in the mountains in the wintertime on sleds, skis, or snowmobiles. In the past, the remote community of Miner’s Basin high in the La Sals was the site of a seasonal mining operation, with some hardy souls overwintering in the snowy basin. In Miner’s Basin’s heyday, it boasted a store, a post office, and lodging for over a hundred optimistic miners.

Gordon Fowler, whose initials are found on the wood of these snowshoes, used these snowshoes to prospect in Miner’s Basin in the La Sals many decades after most others gave up hope of mining riches in the area. Made with a sturdy hardwood frame with rawhide lacing, the snowshoes allowed the wearer to travel over powdery snow without sinking knee-deep. The snowshoes were acquired by the Museum from the estate of Bill Conners, who grubstaked Fowler’s endeavor.

The Moab Museum is dedicated to sharing stories of the natural and human history of the Moab area. To explore more of Moab’s stories and artifacts, find out about upcoming programs, and become a Member, visit www.moabmuseum.org.

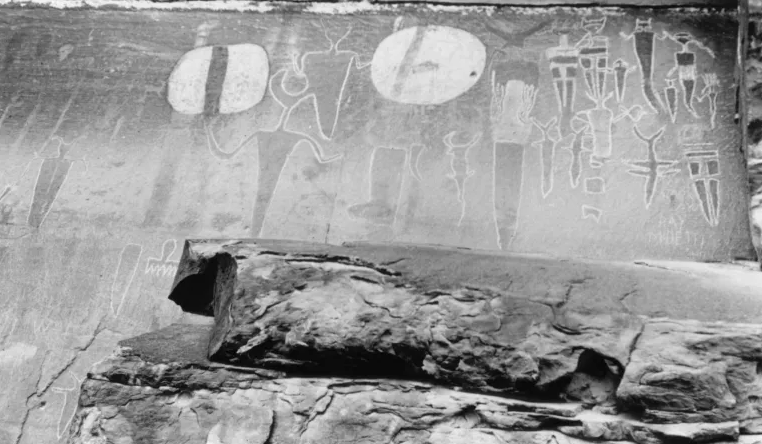

Newspaper Rock [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

Newspaper Rock [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

This is canyon country, a landscape defined by the forces of nature that have carved their way through the red sandstone for millions of years and still continue to perform their work. The human history of this landscape carries a similar throughline: Rock inscriptions carved on canyon walls over thousands of years lend whispers of the history of the people who came before.

Petroglyphs and pictographs across the region preserve thousands of years of human history, spanning many cultures over time. There is much to be learned from these marks pecked or painted onto canyon walls, and they remain important sites for Native communities today.

What is the difference between petroglyphs and pictographs?

Petroglyphs—which are generally more abundant in this area—are images created by carving, engraving, or scratching upon the surface of the rock. Pictographs are painted, consisting of pigment applied to the surface of the stone. While certain panels may have originally been a combination of petroglyphs and pictographs, the windswept sandstone now primarily reveals petroglyphs.

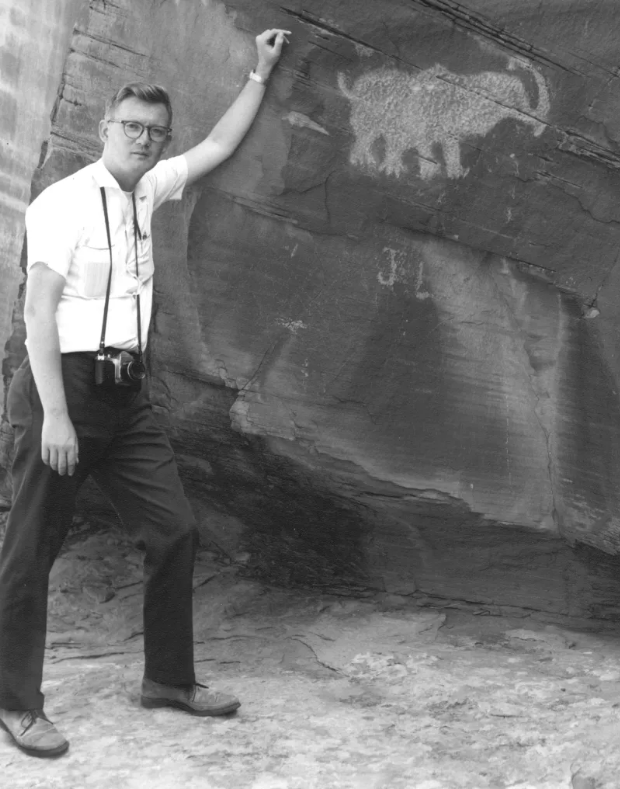

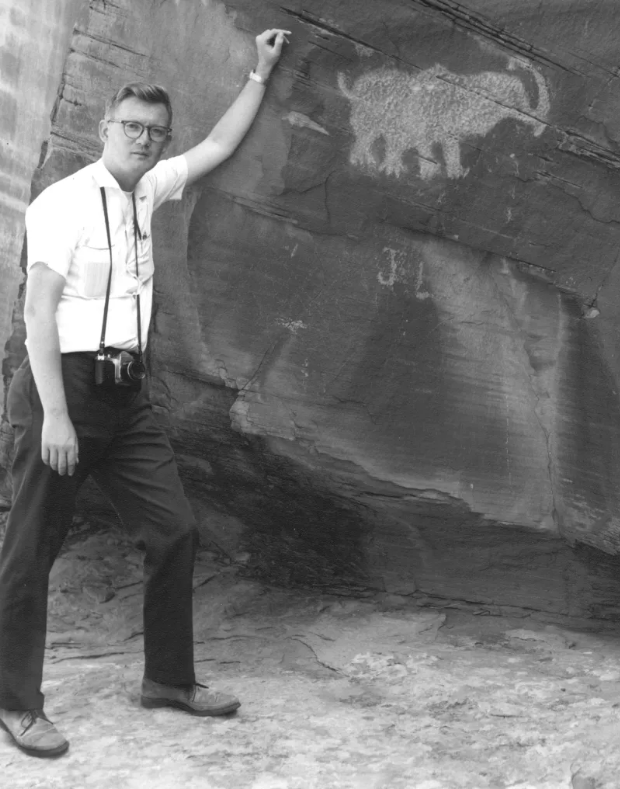

Located downriver from Moab, this rock carving is thought by some to resemble a mastodon, leading some to believe that it was created by people living in the Moab Valley during the late Ice Age. Others interpret the panel as a bear with a fish in its mouth. [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

Located downriver from Moab, this rock carving is thought by some to resemble a mastodon, leading some to believe that it was created by people living in the Moab Valley during the late Ice Age. Others interpret the panel as a bear with a fish in its mouth. [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

What is known about petroglyphs and pictographs?

There are numerous ways to interpret meaning, and inevitably, much of it remains a mystery to visitors today. Native groups with Ancestral ties to the region can offer perspective and interpret meaning from rock writings left many generations ago. Archaeologists also offer a set of ways to interpret these sites.

In the summer of 2021, the Moab Museum presented a temporary exhibition called “Stories on Stone: Interpreting & Protecting Moab’s Rock Imagery” in collaboration with Utah Humanities. The exhibit showcased perspectives about four prominent Moab-area petroglyph panels from Hopi guide and interpreter Bertram Tsavadawa and archeologist Don Montoya.

“There’s always variations of understanding of how sites will be utilized by the Ancestors,” Tsavadawa explained in the exhibit, adding “as a Hopi person, coming from northeastern Arizona to visit and see these sites here, it is reconnecting.”

In a video made with the Museum and the Utah Humanities Council’s Humanities in the Wild initiative, Tsavadawa drew connections between petroglyphs of wavy lines at Moonflower Canyon to the abundant water nearby.

“Water sustains life. Wherever there’s water, you’ll find maybe an Ancestral site, occupation location, or where they were visiting or making their pilgrimages to conduct ceremony, or connect back to nature,” Tsavadawa explained.

Archeologists also offer ways of understanding these traces of the past. A variety of scientific dating methods, including carbon dating, may determine the ages of pictograph pigments. In the absence of pigment, archaeologists can use optically-stimulated luminescence, which tells how long quartz sediments have been exposed to light. Archeologists also recognize distinctive aesthetic styles associated with different periods, such as the Barrier Canyon Style, which allows them to determine the spatiotemporal extent of cultural groups.

Rock imagery sites remind us that history exists beyond the bounds of a museum collection space. Stewardship of sites remains an ongoing topic of community conversation. In April 2021, Birthing Rock, a prominent rock imagery site along Kane Creek Road, was vandalized, inciting community outrage. The vandalism was the second publicized instance in 2021 of petroglyphs in Moab being damaged, the first being a rock climber bolting a route near a 1,000-year-old petroglyph panel near Arches National Park.

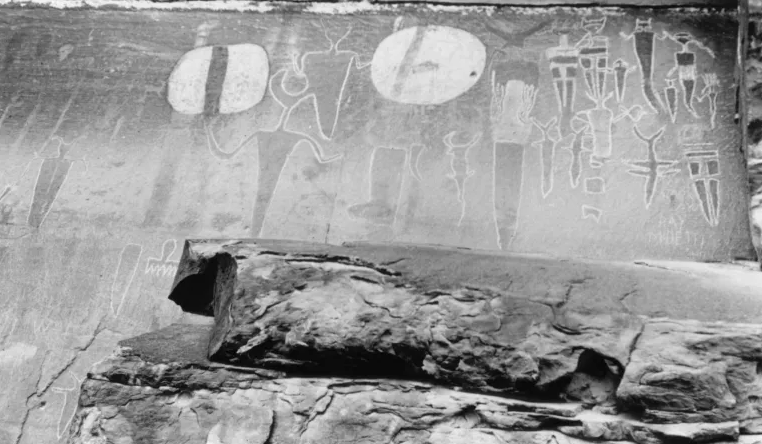

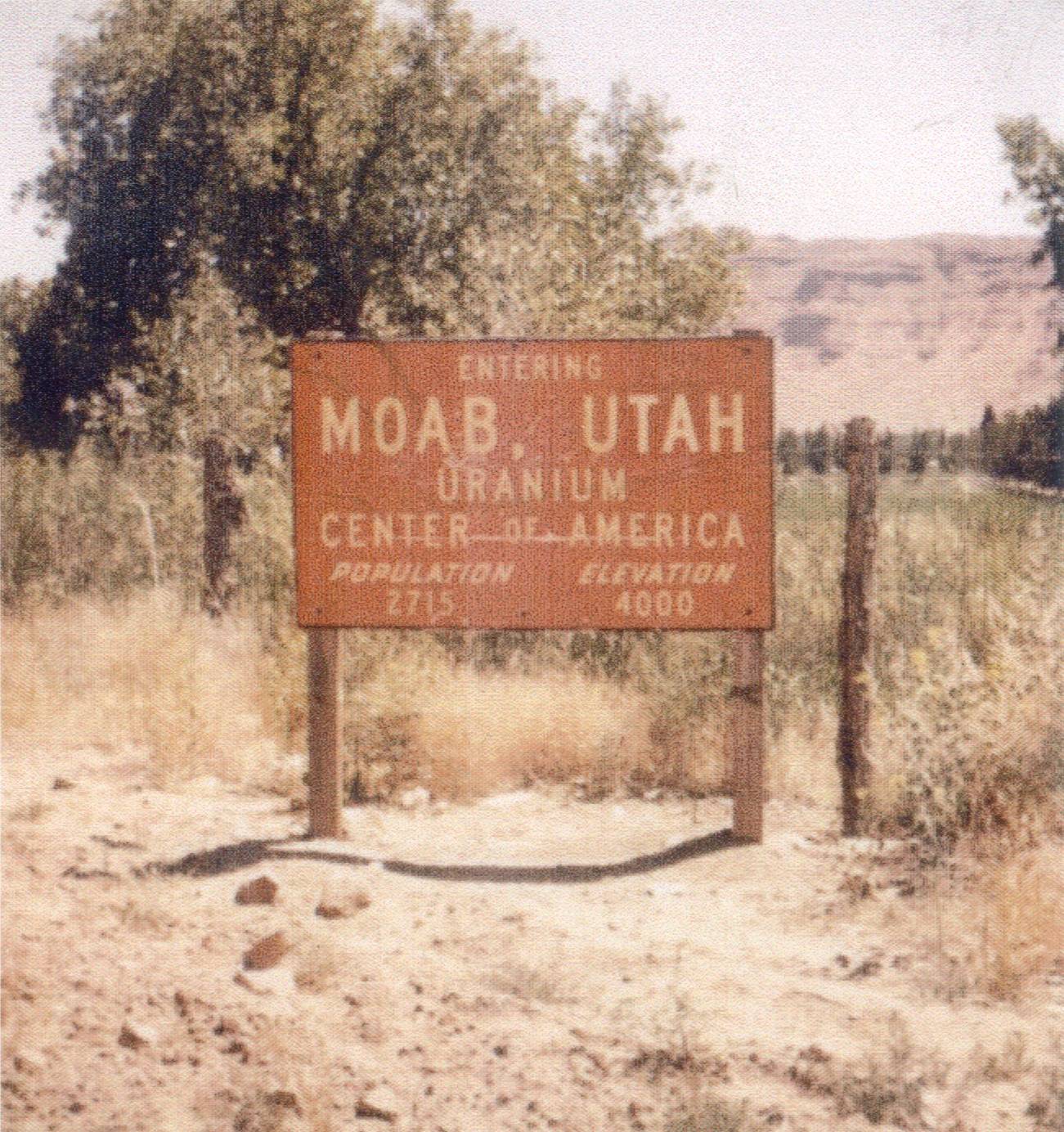

The pictographs at the mouth of Courthouse Wash as it enters the Colorado River represent the Barrier Canyon style, also found at Sego canyon near Thompson Springs. This image was taken before the panel was defaced in 1980. Following the vandalism, the National Park Service cleaned the panel, and restoration work revealed older pictographs beneath the white shields. [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

The pictographs at the mouth of Courthouse Wash as it enters the Colorado River represent the Barrier Canyon style, also found at Sego canyon near Thompson Springs. This image was taken before the panel was defaced in 1980. Following the vandalism, the National Park Service cleaned the panel, and restoration work revealed older pictographs beneath the white shields. [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

Why does it matter to protect rock imagery and Ancestral sites?

In the words of the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition: “To the untrained eye, these archaeological features can sometimes be hard to recognize, but their importance to science, as well as tribal descendants, is immense…More than just a library of human history, this place remains vital to tribal communities across the Colorado Plateau as a place of subsistence, spirituality, healing, and contemplation.”

When visiting these sites, make sure to observe proper visitation etiquette to preserve this history and pay respect to the enduring connections these places provide for Native communities today. These tips, from the Museums of Western Colorado, provide guidance to visitors today:

– Visit rock art sites with respect. Many cultures today see rock art as being just as sacred as it was when it was created.

– Do not touch images. The oils on your hands cause damage that cannot be fixed.

– Take only pictures. Paper rubbing and latex molds cause irreversible damage.

– Respect private property rights.

– Leave archaeological clues found near rock art panels in place. Artifacts such as projectiles can help archaeologists better understand and date the age of panels.

– Report any vandalism to a local land agency such as the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, and Park Service.

The Moab Museum is dedicated to sharing stories of the natural and human history of the Moab area. To explore more of Moab’s stories and artifacts, find out about upcoming programs, and become a Member, visit MoabMuseum.org

The view of the Colorado River from the Moab Rim Trail.

The view of the Colorado River from the Moab Rim Trail.

Charlie Glass atop a horse. [Moab Museum Collection]

Charlie Glass atop a horse. [Moab Museum Collection]

Courtesy of the Moab Museum

Courtesy of the Moab Museum

Gordon Fowler’s snowshoes [Moab Museum Collection]

Gordon Fowler’s snowshoes [Moab Museum Collection]

Newspaper Rock [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]

Newspaper Rock [Moab Museum Collection, Elaine Peterson Collection]